|

View larger image: Right click;

then left click "Open link in new

window." Zoom to 200% or

preferred size.

|

Back in the day when I was a full-time book author, my New York agent enjoyed regaling me with her book-trade "street smarts." Among her favorite and most often repeated aphorisms was this one: There's nothing new under the sun. At the time I regarded this notion with a good deal of skepticism. Personally, I was full of bright ideas that I was pretty sure were brand-new. Certainly I had thought them up on my own without knowingly copying anyone else. But as my years in the book trade mounted, and came to include editing and consulting as well as writing, I began to see what my agent had meant.

What's "new" in nonfiction

In expository nonfiction, a bright idea newly conceived might shed fresh light on related ideas that came before. This can certainly be original and creative but not necessarily brand-new. Forms of creative nonfiction—memoir, biography, popular history, and other kinds of true narrative—have a long history and relative uniformity of structure. Such works are typically organized chronologically, thematically, or by a combination of chronology and theme. Any newness comes from the author's distinctive style and possibly subject matter that is little known or explored from a fresh perspective.

What's "new" in fiction

In fiction, three main kinds of conflict—separately or in combination—drive all stories:

1. Character vs. self (as in, for example, identity confusion, obsession, self-deception, and destructive goals or behaviors)

2. Character vs. character(s) (as evidenced in, for example, jealousy, betrayals, and rivalries of all kinds from office politics to threats of bodily harm to fights to the death)

3. Character vs. major force(s) (for example nature, technology, or apocalypse)

Given that conflict must be present in any functional story, and that there are only three basic kinds of conflict in fiction, it stands to reason that entirely original plots are accordingly limited. Writers, critics, and scholars of literature have long argued about exactly how many distinct plots constitute the entire history of fiction. Widely defended numbers are three, six, seven, twenty, and thirty-six. For more information see, among many other such discussions, the Guardian article ". . . how many basic plots are there in all stories ever written?"

A plausible case can be made for any of the commonly proposed numbers of plots. What this boils down to is that the much-hailed "stunningly original" blockbuster and "creative tour de force" are not completely new but, rather, offer new twists on old plots.

The creative challenge of nothing new

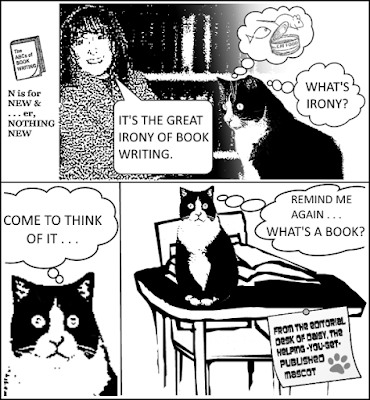

Way back in history, when the literary world was young, entirely new ideas must have been more readily conceivable than they are in our time. If indeed my agent was right, and there is now little or nothing that is truly, totally new, then writers must contend with a notable irony: in this age of sound bites, short attention spans, and constant information flow, a taste for the new is arguably more widely prevalent and insatiable than ever before.

Today's creative challenge is constantly to reinvent what was once brand new, and which must appear to be new all over again. Strategies for recreating the new include the following:

—developing fresh perspectives

—cultivating stylistic distinctiveness

—discovering underexplored subject matter

—concocting new plot twists

—devising compelling hooks

As literary history continues to unfold, new rarely, if at all, means brand-new. The imperative now is ongoing reinvention in writing, and innovation in the marketing of books.

No comments :

Post a Comment