|

View larger image: Right click;

then left click "Open link in new

window." Zoom to 200% or

preferred size.

|

. . . OVERWRITING, that is.

When I edit a book manuscript, I use sidebar comments to explain the reason for many of the changes that I make. Some of these comments include abbreviations to designate frequently recurring issues. My favorite abbreviation of this sort is OW. Not only does it stand for overwriting, but it also expresses a common reader reaction to bloated language. In The Elements of Style, Strunk and White parody the painful effect of "overblown" writing: "Rich, ornate prose is hard to digest, generally unwholesome, and sometimes nauseating."

What is overwriting?

Generally speaking, to overwrite is to write in a contrived, elaborate, and wordy style. Overwritten prose may include any or all of the following lapses, occurring separately or in combination:

—unnecessary adverbs

—excessive and/or redundant adjectives

—obscure and/or overly elevated language

—indiscriminate use of qualifiers (little, very, rather, pretty)

—unnecessarily long sentences

—mixed metaphors and similes: comparisons using dubious logic and contradictory or incompatible imagery

Examples of how to reduce overwriting

In each example below, the reduced version is a representative way to correct the overwritten passage. Other possibilities for reduction are numerous, and rewrites will vary according to the individual writer's style and objectives.

Adverbs

Overwritten: "I hate studying," she said angrily and shut the textbook loudly.

Reduced: "I hate studying," she said and slammed the textbook shut.

Adjectives

Overwritten: A great, huge, overgrown red setter lumbered toward us.

Reduced: An overgrown red setter lumbered toward us.

Overwritten: Weary, and with slow, leaden steps, he plodded onward, dragging himself along the long, endless path.

Reduced: Weary, he plodded along the endless path.

Language

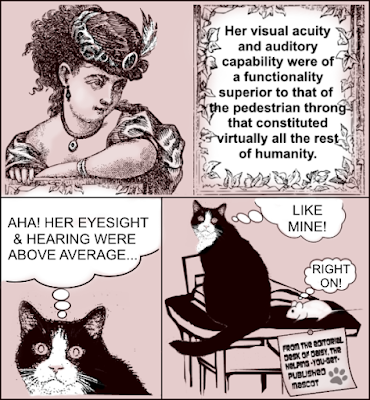

Overwritten: She was in no small way gratified that both her visual acuity and auditory capability were of a functionality vastly superior to that of the pedestrian throng that constituted virtually all the rest of humanity.

Reduced: She was proud that her eyesight and hearing were far above average.

Qualifiers

Overwritten: "The constant use of the adjective little (except to indicate size) is particularly debilitating; we should all try to do a little better, we should all be very watchful of this rule, for it is a rather important one, and we are pretty sure to violate it now and then." (From Strunk and White; boldface added.)

Long sentences

Overwritten: While she couldn't help feeling uneasy, she made an effort to ignore the prickling at the back of her neck, because it could just be heat rash, she told herself in an attempt to stay calm, but she really didn't believe this, as her heart rate was accelerating.

Reduced: She made an effort to ignore the uneasiness prickling at the back of her neck. It could just be heat rash, she told herself, but her accelerating heart rate said otherwise.

Mixed metaphors and similes

Overwritten: Bracing himself like a boxer about to enter the ring, he took a deep breath and then plunged into the poisonously freezing river, which flowed with the ferocity of molten lava from a newly erupted volcano.

Reduced: He took a deep breath and plunged into the freezing river.

Note: The comparisons in the first sentence are dysfunctional, mixing logically unrelated, and thus incompatible, imagery of sport (boxing), toxicity (poisonously), and a natural phenomenon (freezing); the sentence then contradicts the image of freezing cold water by introducing an image of heat (molten lava).

Keep it simple

Avoid overwriting by practicing the necessary restraint to streamline your prose. Without entirely compromising your personal style and vision, lean toward a minimalist approach to writing:

—Reduce or eliminate adverbs; use strong verbs instead.

—Resist introducing extraneous adjectives.

—Use language judiciously, with an eye to transparency.

—Avoid qualifiers; use only those that add to meaning or effect.

—Vary sentence lengths; divide overly long sentences into digestible portions.

—Scrutinize your metaphors for logic, consistency, and appropriateness; when in doubt, opt for a straightforward action statement.

In all matters of style, aim for brevity, directness, and clarity. As Strunk and White advise, "guard against wordiness," self-edit early drafts, and "delete the excess." Less is usually more.